Faced with an object world, on the standard assumption (i.e., that objects are passive or self-contained), the only option a subject has available is trying to direct and manipulate the objects composing that world. Objects have nothing much to contribute, except the details and difficulty of their pliability. Effectively, on this view, objects are virtually waiting around to be consumed, employed, maximized, or optimized. If we relax or eliminate the standard assumption, however, then objects become agents (however alien or inhuman) with which we negotiate in order to achieve various ends or pursue our programs. Negotiation does not preclude direction, but it does necessitate attending to and taking seriously the agency a given object embodies. Objects have their own sinister pathways. Sinister pathways, entangled together, constitute object worlds. And object worlds must be navigated, not simply commanded. Recall that in navigating, one pings or “reads” the landscape in order to determine various locations (e.g., one’s own location, points of reference, the desired destination), conditions (e.g., of passability, of visibility), and pathways forward. Every navigation entails some degree of negotiation with objects, then, and, indeed, the autonomy of objects makes navigation possible in the first place.

In this regard, to repurpose an object of whatever sort entails an experiment or a gambit insofar as doing so is an attempt to test what an object can do beyond its apparent function, limitations, or purpose (i.e., its current prospectus) as inscribed in its descriptive apparatus. Consequently, to repurpose an object means two things: (1) we transform its prospectus into another prospectus and (2) we thereby change its place within the ontological networks that produce and sustain it. Repurposing always requires the intervention of speculative reason – that is to say, of positing a different world than the world we think is given. On the one hand, repurposing is always a function of symbolic translocation (i.e., redescription), which refers to practices of reinscribing or shifting our symbolic formations (e.g., arguments, concepts, injunctions, metaphors, phrases, texts, words, etc.) into jarring or novel contexts. (In at least one sense, we already do this whenever we coin a neologism, fashion an idiolect, mix a metaphor, or even commit a malapropism.) On the other hand, repurposing always effects a functional or material shift in the object as such. Either there’s a shift in what it does, or there’s a shift in what it can do. We err terribly when we think possibilities are irrelevant or unreal, because every object (and every subject, for that matter) is traversing a distribution of possibilities from instant to instant. That something is possible does not make it actual, but its possibility is a necessary precondition for its actualization. Hence, mapping and remapping distributions of possibility is the work of speculative reason. Because thinking is not a ghostly operation that supervenes upon the world without touching it, speculation remains a form of efficacious action – or, rather, it always and irreducibly accompanies what we identify as action in every case.

Accordingly, here’s a speculative attempt at an informal algorithm for repurposing objects (and therefore object worlds).

Step 1: Identify the target object.

Step 2: Explicate the descriptive apparatus attending the target object. (Note: Look especially for sticking points in the descriptive apparatus, which block or impede further negotiations and revisions.)

Step 3: Craft a redescription.

Step 4: Project possible effects of your revision of the descriptive apparatus (i.e., try to determine how the redescription affects the object’s prospectus).

In a preliminary fashion, let’s look at four example objects subjected to repurposing on this model: two technical artifacts (the Phillips screwdriver and earthships), a social construction (the family form), and a temporal category (the future). Hopefully, selecting such disparate objects will indicate something of the wide range of applications of this algorithm and, thereby, its usefulness as a means for conceptual salvage and (re)engineering.

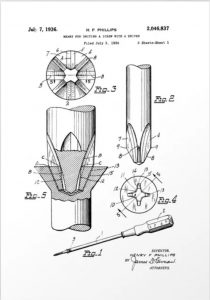

Example 1: The screwdriver

The Phillips head screw drive is a type of cruciform screw drive invented in 1932 (by John Thompson and later sold to Henry Phillips). Phillips head screws have a specific shape, namely, a cross-tip recessed socket, and Phillips head screwdrivers have tips engineered to fit that socket. In contrast to simpler slotted screws (which have a single slot socket suitable for flathead screwdrivers), Phillips head screws have several distinct advantages. Specifically, the Phillips head forces more precise alignments, because the screw and the tip need to be aligned properly in order to reduce angular offset (and, therefore, consequent irregularities in fit), and Phillips head screw drives also reduce the cam out potential (camming out refers to the tendency of the screwdriver tip to exit the screw socket after exceeding a certain amount of torque). In short, the physical form of the Phillips head screw and the Phillips head screwdriver imply each other. They also developed in tandem. They emerge from the same historical timeline of industrial invention and from the same processes of machine-tooling. Attending this abstract object – the Phillips head screw drive, of which any set of matching screws and screwdrivers is an instance or token – is a vast machinic ecology of practices and standards, as well as path-dependent sequences of accidents, decisions, other inventions, and various technical innovations. The Phillips head screw drive doesn’t have a mysterious additional property called its end or purpose, which magically accompanies it, but it does have a specific causal-industrial history that encodes its function heavily into it.

So take a Phillips head screwdriver as our target object. To explicate its descriptive apparatus, we don’t need to understand its history in great deal, but we do need to have a phenomenologically legible sense of what this artifact is – and what it’s good for. That’s part of what it means to live in a culture that knows what a Phillips head screwdriver is. If you can identify one, and you can articulate in use or words what it’s for (i.e., tightening and loosening Phillips head screws), then you’ve already identified it as a target object (Step 1) and (Step 2) explicated its descriptive apparatus (well enough to use it, anyway). Now say you’re not trying to tighten or loosen screws. Instead, you’re trying to pry up a bit of wood. It might well be that prying up a bit of wood would benefit from a prybar, but, if you decide to use a Phillips head screwdriver for prying, it may well suffice. But this necessitates Step 3. In order to use it for this other purpose, you have to craft a redescription of the Phillips head screwdriver, however inarticulately or informally. Here you can see how Steps 3 and 4 often coproduce each other. You want to pry a bit of wood, so you craft a functional redescription of the Phillips head screwdriver by applying it to a problem in a novel fashion. Now it is an artifact whose use has been expanded – that is to say, the object we call a Phillips head screwdriver, which encodes the Phillips head screw drive in the physicalist details of its material composition, is freed up for use and then used.

This is a simple yet paradigmatic case of repurposing in my sense: what an object is changes when its prospectus changes, and the change of prospectus may attend or follow from an alteration in its descriptive apparatus. Redescription is an active maneuver. We navigate object worlds and we negotiate with objects, in no small part, by redescribing them. Note that this does not imply that calling an object by a different name makes it so (names are only a very small part of the descriptive apparatus). Nor does it suggest that a redescription is guaranteed to be successful just because it is a redescription. To the contrary, failures in repurposing are common. A Phillips head screwdriver might work as a prying device, but it isn’t going to be a very good pillow.

Example 2: Earthships

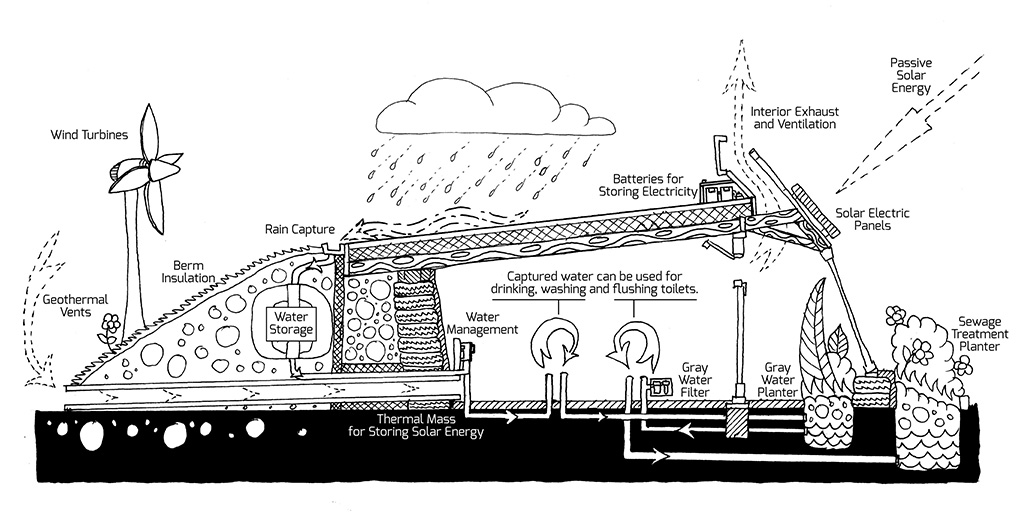

Let’s look briefly at a second technical artifact: the earthship. An earthship is a type of passive solar structure built out of various materials. Their inventor, the architect Mike Reynolds, has a pretty expansive vision of what earthships can do, or what they’re good for, but let’s look at just one dimension of the earthship object. First, there are the facts of their material composition. Consider an earthship largely constructed from soil and upcycled bottles. The old bottles are postconsumer waste products, initially produced in order to function as cheap and easily portable drink containers. After consumption, many of them are lying around as garbage. We can identify used bottles, and we know what bottles are typically for. Knowing what they’re typically for, we can start to play around with redescribing them. Filling the bottles with compacted soil, they become useful as construction materials. They can be repurposed. Redescribing them as construction materials enables the building of earthships, and this redescription, in turn, enables a redescription or repurposing of those objects we call buildings or houses. Hence the expansiveness of Reynolds’ vision (make of this what you will). In any case, this illustrates how redescriptions tend to have multiscalar ripple effects throughout the object world. By contrast, the Phillips head screwdriver example I discuss above is artificially isolated in the extreme – on purpose, as if we didn’t already know that a screwdriver has lots of possible uses. Nevertheless, my point has little to do with epistemology, or what we already know or think we know. In the simplest sense, we know what a screwdriver is for, and we have to suspend what we know in order to repurpose one effectively. But I’m not really interested at the moment in whether or not we’re familiar with a given descriptive apparatus. Instead, my concern is with how repurposing works and, ultimately, how to effectuate or stimulate the repurposing of objects in the broadest possible sense.

Example 3: The family form

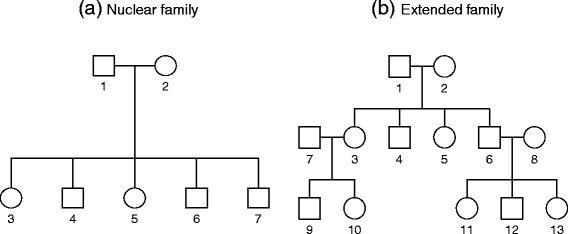

Identify a target object: the nuclear family form, which is still commonly assumed to be among the most given or natural forms of human association. It’s irrelevant that, empirically, families often disintegrate or fail, or else serve as vectors of dysfunction. On the standard assumption, we’ve decided almost unconsciously that blood is always thicker than water. Even many critics of the nuclear family form hold this assumption, and seriously challenging or criticizing it tends to provoke a variety of defensive responses. These range from anecdotal counterassertions (e.g., “well, my family’s not like that”) to scientific misappropriations (e.g., invocations of some assumed genetic imperative) to kneejerk social conservatisms (e.g., claims to the effect that the traditional nuclear family is the core or essential or indispensable unit of civil society). However, it’s worth noting that there’s something fundamentally accidental and necessarily nonconsensual about the nuclear family form. For example, it’s impossible to consult a child prior to her arrival, so family formation involves random assignment. Therefore, the nuclear family form can be in nowise elective. So how might we redescribe the family form (say, in structural terms), so as to enable or propitiate its repurposing and use? As I’ve argued elsewhere, withdrawing our emotional and social attachments from the nuclear family form as the primordial unit of human association frees up the ability to construct elective affinity groups that can do more – that is to say, that can accommodate more types of affective bonds, service opportunities, and social ties than can the nuclear family form. Our attachment to the nuclear family form undermines our ability to invest in novel associations that cohere firmly or reliably. In contrast to the nuclear family form, and its implicit reliance on accidental associations and nonconsensual obligations, consider alternative and repurposed family forms that operate on the basis of bespoke relational options and voluntary obligations. In fact, even suggesting this (and it’s worth noting that, in reality, people already tinker with the family form all the time – although doing so with a consciously or vocally experimental attitude is still generally disincentivized and frowned upon, if not actively discouraged or punished) already constitutes a pretty strong redescription of the family form. If we find it difficult to imagine such an alternative (i.e., denuclearized) family form surviving, then perhaps this is because our culture rabidly perpetuates the narrative that all forms of elective affinity ultimately fail, whereas only the nuclear family form endures, despite its flaws (ironically, especially insofar as it gets ratified in terms of property holdings and their sequestration and transmission).

Example 4: The future

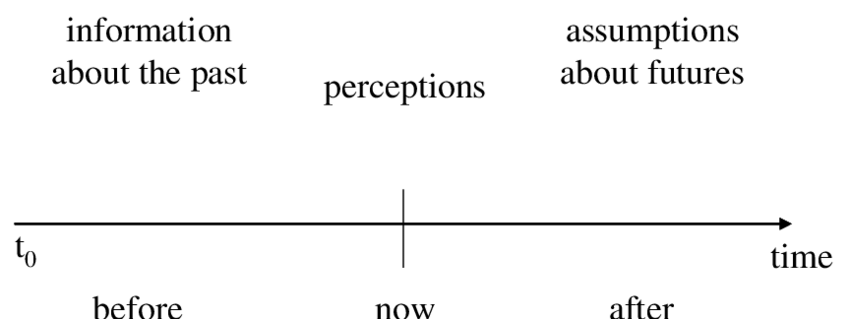

Let’s try it with the future. On one view, the future is a temporal category characterized by its not yet having arrived. On this view, there are three temporal categories or tenses: the past, the present, and the future. Time’s arrow moves forward in a linear fashion, such that the present turns into the future as it proceeds forward and what had been the present becomes the past. As such, the futures we imagine both sponsor, and derive from, our comportment and conduct in the present. By contrast, consider the projection of a future that will retroactively determine its own past – that is to say, the very present from which we project futures (the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan has it this way: “What is realized in my history is not the past definite of what was, since it is no more, or even the present perfect of what has been in what I am, but the future anterior of what I shall have been for what I am in the process of becoming”). This is a fancy way of saying that we can view the present not as mere openness or submission to a plenitude of amorphous futures, but, instead, as the necessary prelude to some specific future. “What is to be done?” becomes “What did we do?” and anxiety becomes necessity. Consider this in more formal argumentative terms. At time t0 there is a specific state of affairs X that is open to a range of possible transformations of X from X1 to Xn. At time tn, X has transformed into some specific state of affairs X’ (being any X value between X1 and Xn). Between t0 and tn, X has changed – but retroactively. At t0, X is the state of affairs that supported a range of possible transformations (from X1 to Xn). At tn, X is the state of affairs that precedes X’. It is only possibly but not patently this X’ at t0. In other words, the future does not have to be pre-scripted, either in terms of its content or its form. In this regard, I suggest that we need to destroy this object called the future: we need to learn to think like an apocalypse. As the apocalyptic imaginary takes shape for us, we foresee Anthropocene futures afflicted by catastrophe, devastation, and failure. However, the future as such – the real object – will survive its apocalypse. As James Berger notes of the apocalyptic imagination more generally:

[…] nearly every apocalyptic text presents the same paradox. The end is never the end. The apocalyptic text announces and describes the end of the world, but then the text does not end, nor does the world represented in the text, and neither does the world itself. In nearly every apocalyptic presentation, something remains after the end. In the New Testament Revelation, the new heaven and earth and the New Jerusalem descend. In modern science fiction accounts, a world as urban dystopia or desert wasteland survives. […] Something is left over, and that world after the world, the post-apocalypse, is usually the true object of the apocalyptic writer’s concern.

Through the work of the apocalyptic imagination, then, the future as an object can become freed up for its use in the present. My claim here is that using the future as an object makes possible political forms of life that can potentially address, recuperate, and survive the trials and tribulations of the present. This is a way of saying that it’s as if the apocalypse has already occurred – not because all is lost for us, but because our catastrophes and revelations alike make manifest the underlying logics driving us into disaster.

Excursus 6: Recursion

Go back to Part 3 “Excursus on creative destruction (Spielrein, Schumpeter, Boyd, Land)” or go forward to Part 5 (“Postface on chirality”).